By: James S. Gordon, MD

Eight-year-old Sofia, whose picture I shared with you yesterday, sits beside me in July, in a park in Irpin, next door to Bucha, in a now placid neighborhood where earlier in 2022, Russian soldiers massacred hundreds of civilians.

I’ve asked Sofia what the war was like for her before she and her family, like so many families in Irpin and Bucha, fled.

“Terrible,” she says, making a small, sour face. Then, as I wait for more, she repeats it, “Terrible.”

I want to know more, and I know, as a psychiatrist who has worked with children during and after wars for 30 years, that words about terrifying experiences don’t come easily. “Would you draw ‘terrible’ for me?” I ask, sharing a piece of paper and crayons.

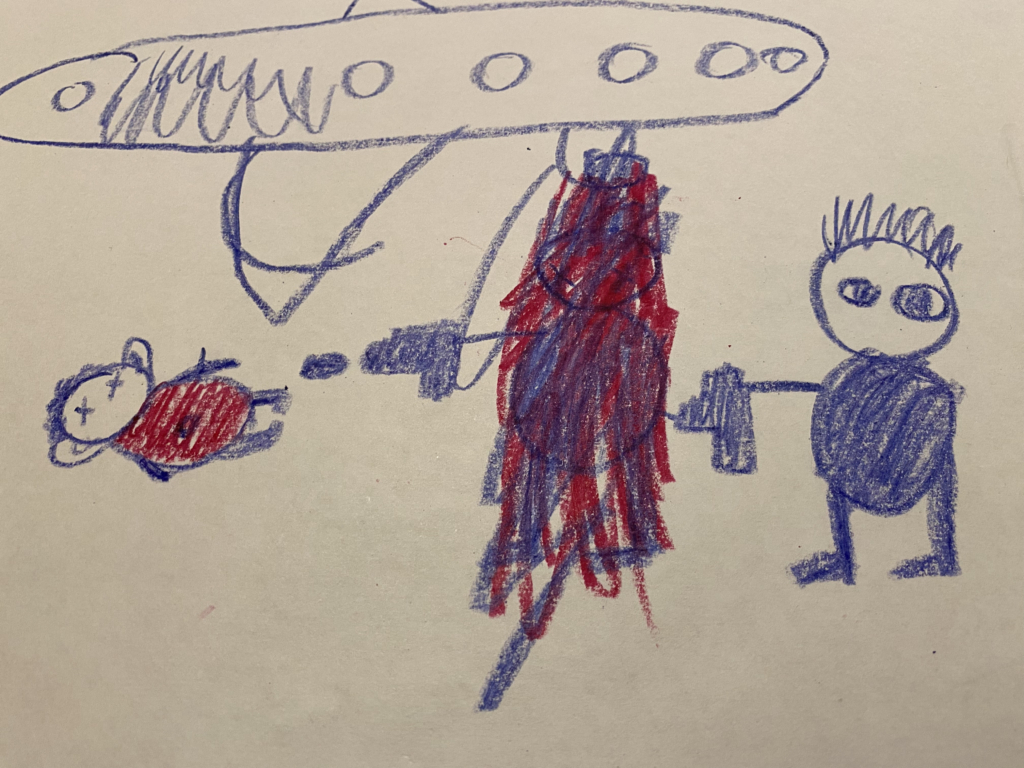

Sofia bends to the task. She draws a small, child-size body, eyes closed, covered in the red of blood, lying on the ground. Next, a vertical figure standing over the body, holding an automatic weapon. “This,” she tells me, “is the Russian soldier who killed the girl.” Behind him rises a third figure, a Ukrainian soldier, who, she says, with some satisfaction, shoots the Russian.

We sit together silently, contemplating the murder and revenge Sofia has summoned up. It’s a lovely day, with chestnut blossoms filling the limbs of tall trees, perfuming the air.

Sofia picks up another crayon, draws a plane flying low above the figures. Suddenly, she scribbles a burst of red on the Russian soldier. “Now, I believe he’s really dead,” she says in a voice that is as uncertain as it is hopeful.

Sofia’s drawing haunts me as I listen to other children. They have heard that Russian soldiers have killed children, and, like Sofia, they fear that nothing, not even brave Ukrainian soldiers, will permanently remove this alien menace.