An exclusive excerpt from Food As Medicine faculty member Dr. Ludwig’s new book Always Hungry? available here!

David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD, is a practicing endocrinologist and researcher at Boston Children’s Hospital, Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, and Professor or Nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Ludwig is also a faculty member of CMBM’s Food As Medicine program. He has provided the CMBM community with an excerpt from his new book (below) and you can get a taste of his work in an op-ed he wrote in The New York Times in 2014.

You can also find out more about Dr. Ludwig and his book Always Hungry? on his Web Page, Twitter, Facebook, his Medium blog, and his YouTube channel.

The following text is excerpted from the book Always Hungry? by David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD. Copyright © 2016 by David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD. Reprinted by permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1 Excerpt for CMBM readers

I completed my medical training in the 1990s, as the obesity epidemic approached crisis proportions. Incredibly, two out of three American adults had become excessively heavy. For the first time in medical history, type 2 diabetes (previously termed “adult onset diabetes”) had begun striking children as young as ten years old. And economic forecasts predicted that the annual medical costs of obesity would soon exceed $100 billion. Amid these disturbing developments, I decided to specialize in obesity prevention and treatment.

I completed my medical training in the 1990s, as the obesity epidemic approached crisis proportions. Incredibly, two out of three American adults had become excessively heavy. For the first time in medical history, type 2 diabetes (previously termed “adult onset diabetes”) had begun striking children as young as ten years old. And economic forecasts predicted that the annual medical costs of obesity would soon exceed $100 billion. Amid these disturbing developments, I decided to specialize in obesity prevention and treatment.

Like many young doctors, I had received virtually no instruction in nutrition. Then, as now, medical schools focused almost exclusively on drugs and surgery, even though lifestyle causes most cases of heart disease and other chronic disabling conditions. In retrospect, my lack of formal knowledge of nutrition was a blessing in disguise.

The 1990s were the height of the low-fat diet craze, exemplified by the original Food Guide Pyramid, published in 1992. Based on the notion that all calories are alike, the pyramid advised us to avoid all types of fat because they contain twice the calories of other major nutrients. Instead, we were told to load up on carbohydrates, including six to eleven servings each day of bread, cereal, crackers, pasta, and other grain products. Luckily, I hadn’t been indoctrinated in these conventional teachings and began my career in research and patient care with an open (and mostly empty) mind when it came to nutrition.

My first professional research position was in a basic science laboratory conducting experiments with mice. Soon after starting this work, I became amazed by the beauty and complexity of the systems that control body weight. If we fasted a mouse for a few days, it would, of course, lose weight. Then, when given free access to food, the animal ate voraciously until it had regained all of the lost weightâno more, no less. The opposite was also true. Force-feeding could temporarily make a mouse fat, but afterward it would avoid food until its weight dropped back to normal. Based on these and other experiments, it seemed as if an animal’s body knew precisely what weight it wanted to be, automatically altering food intake and metabolism to reach a sort of internal set point, like a thermostat that keeps a room at just the right temperature.

Our most interesting scientific experiments explored how this body weight set point

could be manipulated. If we modified certain genes, administered drugs, or altered diet in particular ways, the mice predictably gained weight to a new stable level. Other changes caused permanent weight loss, without apparent signs of distress. These experiments demonstrated a fundamental principle of the body’s weight-control systems: Impose a change in behavior (for example, by restricting food), and biology fights back (with increased hunger). Change biology, however, and behavior adapts naturallyâsuggesting a more effective approach to long-term weight management.

In the midst of my stint in basic research, I helped develop my hospital’s newly established family-based weight management clinic, called the Optimal Weight for Life (OWL) program. Like virtually all specialists at the time (and many to this day), our team of doctors and dietitians focused at first on calorie balance, instructing patients to “eat less and move more.” We prescribed a low-calorie/low-fat diet, regular physical activity, and behavioral methods to help people ignore hunger, resist cravings, and stick with the program. When they returned to the clinic, my patients usually claimed to have followed recommendations. But with few exceptions, they kept gaining weightâa depressing experience for everyone involved. Was it the patients’ fault for not being honest with me (and perhaps themselves) about how much they ate and how little they exercised? Or was it my fault for lacking the skills to motivate patients to change? I felt ashamed of judging my patients negatively and felt like a failure as a physician. I dreaded going to the clinic, and I’m sure some of my patients felt the same way. I suspect many doctors and patients at weight loss clinics throughout the country can relate.

After about a year of this schizophrenic existenceâfascinated with biology in the lab, frustrated with behavior change among my patients in the clinicâI began to wonder about the disconnect. Why did basic scientists think one way about obesity and practicing clinicians another? Why did we disregard decades of research into the biological determinants of body weight when treating patients? And why were we using an approach to weight loss based on a “calories in, calories out” model that hadn’t changed since the late 1800s, when bloodletting was still in vogue?

After about a year of this schizophrenic existenceâfascinated with biology in the lab, frustrated with behavior change among my patients in the clinicâI began to wonder about the disconnect. Why did basic scientists think one way about obesity and practicing clinicians another? Why did we disregard decades of research into the biological determinants of body weight when treating patients? And why were we using an approach to weight loss based on a “calories in, calories out” model that hadn’t changed since the late 1800s, when bloodletting was still in vogue?

So I launched into an intensive examination of the literature, from popular diet book authors like Barry Sears (The Zone Diet) and Robert Atkins (Dr. Atkins’ New Diet Revolution) to George Cahill, Jean Mayer, and other preeminent nutrition scientists of the last century. I spent hundreds of hours poring over musty volumes in Harvard’s medical library, rediscovering provocative but neglected theories about diet and body weight. And I began to realize just how little evidence there was to support standard obesity treatment.

Soon, my entire perspective shifted. I came to see food as so much more than a delivery system for calories and nutrients. Although a bottle of cola and a handful of nuts may have the same calories, they certainly don’t have the same effects on metabolism. After every meal, hormones, chemical reactions, and even the activity of genes throughout the body change in radically different ways, all according to what we eat. These biological effects of food, quite apart from calorie content, could make all the difference between feeling persistently hungry or satisfied, between having low or robust energy, between weight gain or loss, and between a lifetime of chronic disease or one of good health. Instead of calorie counting, I began to think of diet in an entirely different wayâaccording to how food affects our bodies and, ultimately, our fat cells.

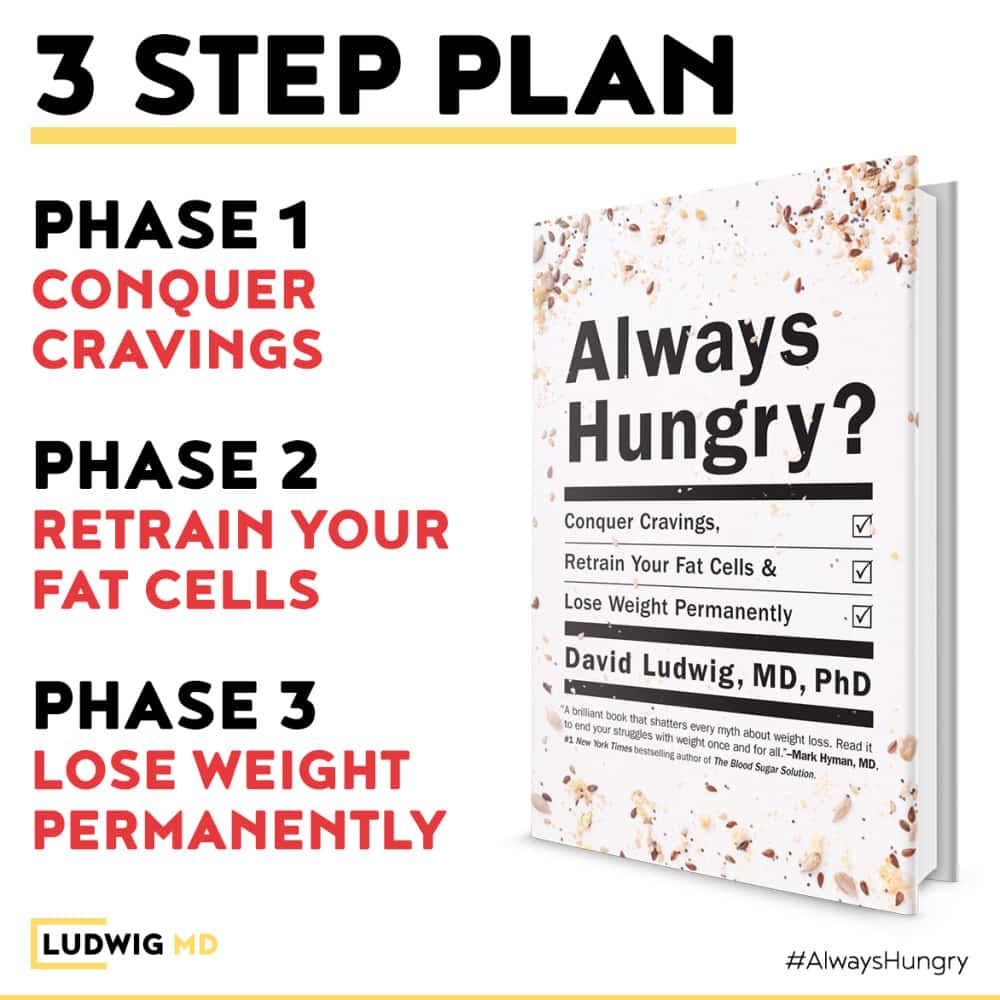

In Always Hungry?, I explore this radical new science of body weight control. And I provide a 3-phase program that let’s you lose weight without calorie counting â by putting biology back on your side!

Excerpted from the book Always Hungry? by David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD. Copyright © 2016 by David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD. Reprinted by permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved. Available at Amazon.com.